As of press time three of the reigning NCAA Division III National Championship players remained in the hospital recovering from rhabdomyolysis, or, as it's more simply known, "rhabdo," Tufts officials said. Nine players required hospitalization, and experts say it should not have gotten to this.

Update: The Boston Globe reported Wednesday, Sept. 25, that all of the players have now been released from the hospital.

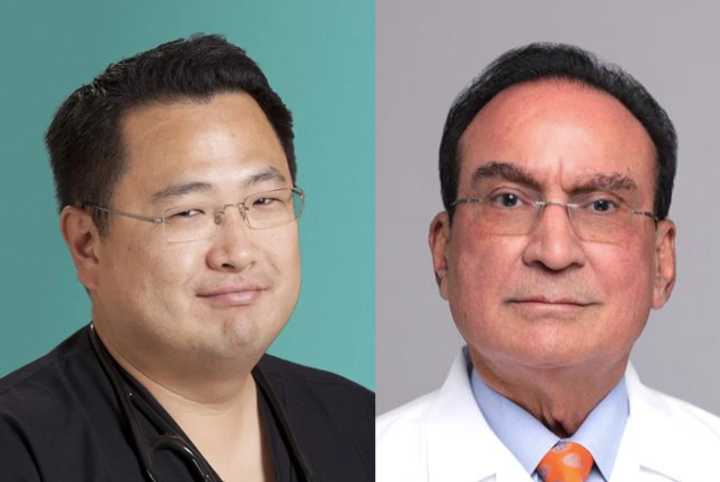

Rhabdo is caused when muscles break down and release toxins into the bloodstream and overwhelm the kidneys' ability to excrete them, said Dr. Tae Park, the director of emergency Medicine at Holy Name Medical Center in New Jersey.

Dr. Sushil K. Mehandru, Section Chief of Nephrology at Jersey Shore University Medical Center & Professor of Medicine at Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine, says it's caused either by pressure on the muscles, extreme muscle exertion or muscle injury.

"When [the athletes] are being exercised to the maximum extent, they may develop acute muscle pain and cramps," he said. "Boys won’t admit they have severe muscle pain. They are macho. They will keep walking until they can’t walk and that’s what happens."

The athletes likely continued exercising until they physically couldn't, the physician continued: "They can't move because the muscles swell up."

In addition to muscle soreness and swelling, other symptoms of rhabdo include pinkish-reddish urine, a drop in blood pressure, and high blood levels of a protein called creatine phosphokinase (CPK), which Mehandru described as dissolving muscle tissue.

Mehandru said patients can lose gallons of fluid, which moves from the blood directly into the muscles that are breaking down.

Rhabdo is treated with normal saline intravenously to increase blood volume, Mehandru said. And, the sooner the better.

"Fluid goes out of the vessels and into the cells that had been injured," Mehandru explained. "Blood volume has shrunken, so by giving IV, you're giving blood volume, and blood pressure rises."

Recovery time depends on how quickly patients can get IV fluids, Mehandru said. He recommends telling an ambulance to bring saline, so treatment can start right on the field.

"Their prognosis will be much better than the [patients] who took three to four hours to get the saline," the physician said. "If the delay is more than six hours, that is more likely to cause acute kidney injury."

Tufts University remained tight-lipped about the extent of the athletes' conditions. A university spokesperson said only that the school is "monitoring their progress."

“The team is a tight-knit group of young men who have shown remarkable resilience, understanding, and care for each other throughout this episode,” Patrick Collins said. “We will continue to monitor and work with them closely, and we hope for a rapid return to good health for all involved.”

Rhabdo isn't only caused by extreme exertion, according to Dr. Supreet Kaur, who works alongside Mehandru in JSUMC's nephrology unit.

"We do see a lot of rhabdo cases because it’s not age-specific," Kaur said. "We see in older people who fall, intoxicated individuals laying on the same group of muscles, or stroke patients laying in the same position for hours. In youngsters who exercise more than they can tolerate.

Kaur and Mehandru discovered a syndrome, published in the Journal of Clinical Review & Case Reports, that involves rhabdomyolysis and kidney disease now called Supreet/Mehandru Syndrome. The research allows physicians to predict kidney disease in rhabdomyolysis cases.

Tufts has deferred answering most questions as the Medford, Massachusetts, school has hired an independent investigator to determine what happened that day.

The alumni who led the workout that day was a recent graduate of the US Navy's elite Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL course. It's unclear if he possesses any certification in exercise science or physical therapy.

A call for comment from the US Navy seeking comment was not immediately returned.

Click here to follow Daily Voice Lenox-Lee and receive free news updates.